Supporting UK farmers towards net-zero agriculture

- Centre for Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Studies

This article was originally posted on Yorkshire Bylines.

In this article, Dr Peter Gittins, farmer and expert in rural entrepreneurship, provides an opinion piece on the complexities faced by farmers in England during their transition away from the basic payment scheme (BPS). The article discusses the challenges associated with concerns raised by farmers regarding the rollout of the new environmental land management schemes (ELMs) and increasing legislative and societal pressures for agriculture to meet net-zero ambitions. This piece is based on the preliminary findings of a research project being carried out at the University of Leeds.

Transitioning away from basic payments scheme

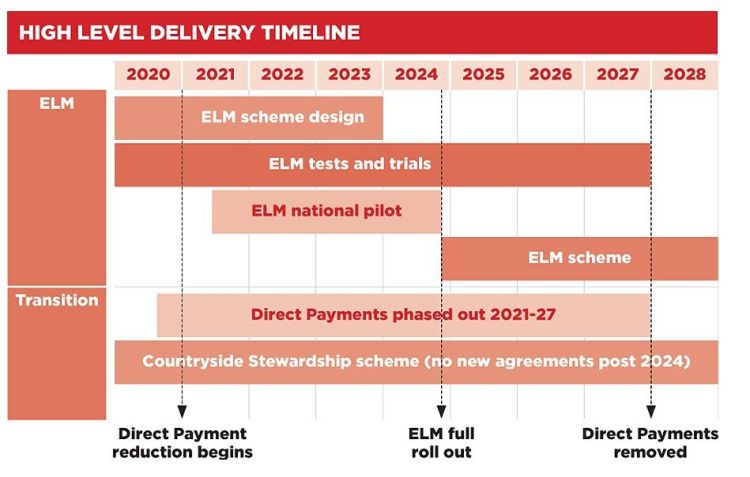

Brexit commenced in 2016, and Article 50 was triggered in 2017, initiating the official leaving process. ELMs were announced as a replacement for the European’s BPS. In England, a seven-year transition plan was then implemented, introducing progressive reductions in subsidies for farmers. By 2028, subsidies will be completely removed. This is a major concern for many farmers, as funding under the common agricultural policy (CAP) has provided UK farmers with approximately £3bn per annum, making the CAP the single largest expenditure of the EU budget. The removal of this critical financial resource is a complex issue and will impact farmers differently.

Figure 1- ELMs rollout

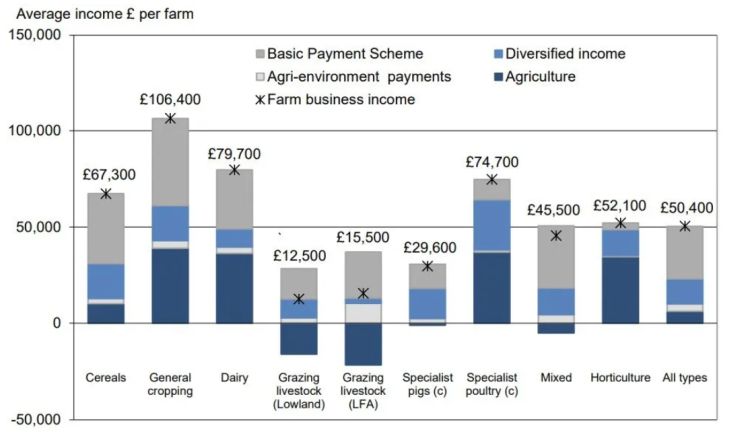

Many average-sized farmers are reliant on these subsidy payments. In some instances, subsidies can comprise 90% of a farmer’s annual business profit. Many farmers make a net loss without subsidies, and the removal of them could lead to business collapse for some. In 2018, for example, upland farmers, on average, had an annual farm business income of just £15,500, inclusive of subsidy support (see figure below).

On our farm, we are already feeling the progressive reductions of BPS, especially considering the rising cost of living. For others, I imagine it will be much worse.

Figure 2 – Farm business income 2018/2019

But it wouldn’t be fair to say that all farmers are in favour of subsidised support: subsidies are controversial. The manner in which BPS payments were calculated favoured those with more land—the more land one has, the more entitlements and subsidies. Large landowners do best: entrepreneur James Dyson has received over £5mn in subsidy support payments alone.

Smaller-sized farmers and tenant farmers, in particular, have been particularly constrained. As payments are area-based, smaller farmers receive less income. Tenant farmers often argue that subsidies have caused either inflated land prices or restricted access by landowners. Defra cited this issue as a key driver in the decision to move away from subsidising land ownership. Moreover, some farmers have argued that, while subsidies are important for their businesses, BPS has inadvertently sustained many failing farming enterprises that should not continue operating. For some, a change to the system is welcome.

The removal of subsidies could have unintended consequences, necessitating strategic planning to compensate for income loss. Farm entrepreneurship strategies will likely play an important role in helping farmers respond effectively to compensate for the loss of this critical financial resource. Diversification could be a suitable choice for some, both within and outside of agriculture. Many are turning towards diversification to combat increasing economic issues in the sector. But to diversify effectively, farmers must learn new skill sets beyond conventional farming and navigate new sets of constraints, such as dealing with increasing levels of bureaucracy and legislation.

Many farmers will now be beginning to think if the ELMs will work well with their business practices.

Transitioning to ELMs

Many farmers have raised concerns about finances under the new schemes. Several farmers I spoke with told me about the value of receiving cash directly under the BPS system, which can be used for immediate farming purposes. ELMs are somewhat more complex. Farmers have expressed apprehension regarding the bureaucratic complexities associated with prior agri-environment schemes (AES).

Farmers need to assess their land types, explore the various options under each scheme, and evaluate how well their land aligns with these new schemes. This becomes even more complicated when many farmers are already in existing countryside stewardship agreements (with many extended for a further five years). Conflicts can arise between the existing and new schemes.

Indeed, for older and more traditionalist farmers, it will be a challenging time. Moreover, not all farmers possess the required skill sets, necessitating the outsourcing of such activities to land agents, often incurring excessive costs. Misunderstanding information can also have consequences, leading to penalties and fines – something we have experienced.

On a personal note, as an academic with a PhD and a farming background, I found interpreting the 117-page guidance document on the sustainable farming incentive (SFI) to be excruciatingly challenging. Considering that four in ten farmers are over the age of 65, I cannot begin to comprehend how some farmers will manage this. Many farmers do not use computers, mobile phones, or the internet. Local and regional farming networks and associations play a crucial role in disseminating information, but not all farmers participate in such networks. This raises concerns about how to best reach these socially excluded, yet equally important, groups of farmers.

While many farmers are approaching change with a positive mindset and are adapting as best as they can, the Farming Community Network (FCN) is aware that ‘information overload’ can be a challenge. FCN is a national charity that supports farmers and farming families during difficult times and in preparing for change. Its volunteer network across England and Wales comprises people with close links to agriculture, who, vitally, speak ‘the language’ of farming and understand the unique pressures that come with the job. FCN coordinates a range of initiatives and activities to bring farmers together, encouraging them to take a proactive approach to forward planning. Local events such as farm walks, breakfasts or group meetings can be an effective way of encouraging different ideas and helping to disseminate information.

Important information is often written academically and can be difficult to access unless you know where to look; or it requires a strong familiarity with how to use the internet to find exactly what you need. Working out what changes in policy can mean for the individual farmer or farm business can be challenging, and there is a risk that some within farming could be left behind rather than brought along on this journey. FCN regularly hears from farmers who are worried about the future, and the charity plays an important role in ‘walking with’ people to help them find a positive way forward. FCN has collaborated with researchers at Leeds University Business School to greater understand the challenges facing farmers.

Broader implications of net-zero for the agricultural sector

One core concern facing farmers is the level of new regulations and legislation being imposed on their business and personal lives. Many farmers I have spoken with have questioned whether the UK is pushing environmental regulation on farmers too far. The UK is the first major economy to legally commit to decarbonising all sectors by 2050. Despite the UK only contributing 1% to total global greenhouse gas emissions, agriculture is providing food, fibre, and environmental services, using “public money for public goods”, as Michael Gove puts it. Of course, there will be an environmental cost, but farmers are producing commodities and essential services.

Net-zero brings many uncertainties for farmers. What does this national commitment truly entail for farmers, and how will it affect them at the farm level? This is where farmers require clear guidance from rural policymakers.

Regarding net-zero, farmers’ views are mixed. Some farmers have raised concerns over government trust, expressing worries about how the UK government will meet these emissions targets. They state that farms could be lost due to offsetting practices—an apprehension also shared in Wales. Indeed, this concern is also shared in the Netherlands, where farms are being bought out in the name of emissions reductions. The UK government should support farmers by making their message clearer, stating that meeting net-zero will not put farming, specifically livestock businesses, at risk. The loss of the small family farm is a concern. Since 2005, we have lost 5.3 million farming businesses in Europe.

Investment costs are both concerning and uncertain. ‘You can’t go green if you’re in the red’ is a key message echoed among farmers. No farm will put itself out of business in the name of environmentalism. Farms are businesses at the end of the day and have to balance competing economic, environmental and social issues. But in reality, few farmers know just how close they are to achieving net-zero or if the measurements will change in the coming years. This makes strategic planning difficult.

There are also broader social implications that net-zero might have for farming practices, and we must tread lightly here. Things that appear environmentally friendly may not be, with trade-offs occurring between greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction and biodiversity. For example, extensive livestock systems (farming in areas with low agricultural productivity relative to the area being farmed) provide a wealth of animal welfare and ecological benefits, yet often result in higher GHG emissions than intensive practices where livestock can be finished in shorter timeframes. But which is better?

Too much emphasis on environmental benefits could come at the social and cultural sacrifice of other important practices.

Entrepreneurial opportunities via ELMs and net-zero agriculture

It is very easy to paint a pessimistic image of farmers adapting to ELMs, but some I have spoken with are optimistic. Some farmers are already actively engaged with AES and welcome new opportunities. These farmers are invested in conversations around regenerative agriculture, agroforestry practices, and sustainable intensification. For them, ELMs will likely provide more opportunities to get paid for the things they are already doing.

There are financial opportunities associated with net-zero, such as renewable energy diversification, new options under ELMs tiers, alongside opportunities to farm with fewer inputs and enhance productivity gains. The financial benefits are an additional advantage if it means we will have a positive impact on the climate crisis, resulting in fewer weather disasters.

But for me, the most fundamental question is: How will ELMs be applicable to all the different types of farmers?

This is important because farmers do not have to engage; ELMs is a choice. But Defra has high ambitions, wanting 70% of farmers in SFI by 2028. A lack of engagement with the schemes could result net-zero ambitions falling short. Defra needs to recognise the heterogeneous nature of farmers and incorporate options for all types of farmers, not just financially rewarding environmental sustainability.

Farmers I have spoken with call for more options under SFI that reward social and culturally important farming practices, linking to the sixth public good of enhancing beauty, heritage, and engagement with the natural environment. From this work, I have a set of recommendations around this that I will present in a separate article and policy document, suggesting ways to incorporate them into ELMs.

I am also not convinced that progressive reductions were the best course of action, especially for farmers who are already struggling financially. George Eustice said, “We should not cling on to the sinking ship that is the CAP”. But where are we headed instead? If the CAP is akin to a sinking ship, as Eustice states, does that imply that the agricultural transition plan is the life raft? A punctured raft slowly losing air (subsidies) as time passes for some? And are ELMs the island spotted in the distance, and is that island a paradise or a place of the unknown?

In conclusion, as farmers navigate the complexities of transitioning to ELMs and embracing the path to net-zero, it is essential to ensure inclusive and flexible schemes that reward diverse farming practices, preserve social and cultural values, and provide financial stability, ultimately leading to a sustainable and resilient agricultural sector.

Contact us

If you would like to get in touch regarding any of these blog entries, or are interested in contributing to the blog, please contact:

Email: research.lubs@leeds.ac.ukPhone: +44 (0)113 343 8754

Click here to view our privacy statement

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the views of Leeds University Business School or the University of Leeds.