The rural cost of living crisis: Exploring the constraints facing hill farmers in England

- Centre for Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Studies

UK Cost of Living Crisis

This winter, many are struggling with the ongoing cost of living crisis, influenced by the war in Ukraine. Inflation, increasing electricity bills, and rising fuel prices are prompting many to reassess their household budgets. Usage of UK foodbanks remains high, with many families turning to credit to pay increasing debts.

The UK government has provided some measures to individuals and businesses, such as the £150 council tax reductions, £650 cost of living payments and a £400 energy rebate in response to (another) rise in the price cap. However, the economic pressures are mounting, with rural inhabitants being particularly affected.

Rural Life

In the UK, there are an estimated 551,000 rural businesses that employ roughly 3.7 million people operating in various sectors, including agriculture, tourism, equestrian services and pubs. In England, approximately 11.7 million people live in rural areas, equating to 21% of the population, contributing £261 billion to England’s economy.

Rural areas offer great economic potential, with some rural regions being found to have higher levels of entrepreneurial activity than some urban regions. However, for those living in rural areas - especially during the cost of living crisis - it can be a challenging environment.

Rural areas have a higher number of older aged people (a group particularly at risk this winter). Geographical isolation can also be a challenge, with rising issues surrounding mental health. Figures indicate that inhabitants might be impacted more than those living in urban regions during the cost of living crisis. People in urban areas typically receive higher incomes than those living in rural UK regions. This inequality is also noted on a global scale, with many societal challenges, such as poverty, being a predominantly rural problem.

While rural wages remain low and lag behind salaries in urban regions, costs in rural areas remain high. Transportation infrastructure remains underdeveloped, requiring inhabitants to spend more on necessary travel to work. Indeed, many rely on cars as their main source of transportation, with rural households spending approximately £114 per week on transport.

Home heating costs are also higher, with many rural houses being poorly insulated and being off-grid from main gas lines, reliant on other solid fuel sources, such as burning wood and coal.

Crime too has also been linked to the cost of living crisis, with the annual rural crime report by NFU mutual showing rates returning to pre-pandemic levels. Livestock, machinery and fuel theft are reported concerns for farmers.

Farming and the rising cost of living

On our farm, a 250-acre upland farm in West Yorkshire run by my father, brother and myself, we are also experiencing the rising costs of living. The price of red diesel has reached record highs, up from below 50 pence per litre (2019) and now reaching £1.02 a litre. A significant increase and especially hard-hitting on our finances, considering that we need 6000 litres per year for our machinery.

The price of coal has doubled, with quality solid fuel (wood) becoming more difficult to source. We are off mains gas supply and rely exclusively on our log burner for heating. Animal feed and building materials have all increased too, in alignment with rising agricultural inflation. While we received half of our Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) early this year, a measure introduced by the UK government to ease farm cash flow, we are still feeling the pinch.

These rising input costs, alongside dwindling farm income following the yearly reductions in BPS payments, are creating the perfect storm which will likely make it difficult for some farmers to survive. Indeed, for those eligible farmers, a lump-sum exit could have been a dignified way out.

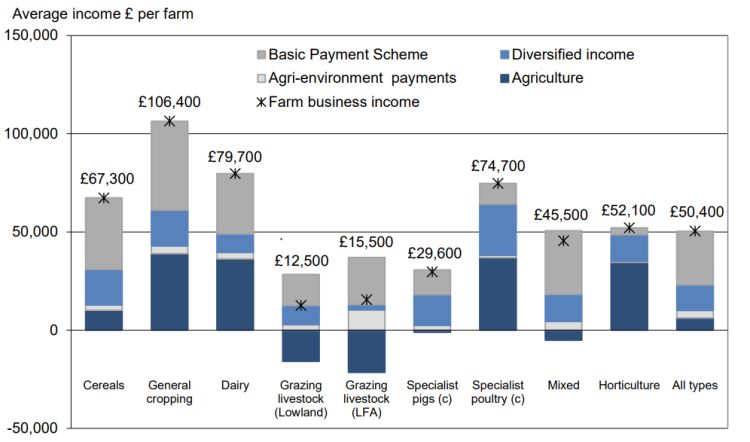

Rising inflation and the phasing out of BPS payments could contribute further to the declining number of farm holdings across Europe. Upland farmers in Less Favoured Areas received an annual business income of just £15,500 in 2018, making a net-loss on agricultural activities and subsidies comprising the majority of their annual farm business income. In some instances, subsidies can comprise up to 90% of a farmer’s annual income.

(Figure 2 Defra Farm Business Income 2018/19)

Supporting UK farmers

Farmers, like other business owners, need to develop resilient and profitable business models. Academic research highlights that many farmers often lack competitive and entrepreneurial skillsets. Developing these skill sets will allow farmers to identify and exploit new market opportunities.

Various agricultural stakeholders, such as the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) with their strategic farm events, run practical workshops to assist farmers in developing these skills.

Universities, particularly educators in entrepreneurship studies and strategic management, could be especially useful in helping develop farmer skill sets. This is something I am currently pursuing through my current research activities via the Leeds University Business School Impact and Engagement Support Fund.

Changes in consumer purchasing habits could help farmers financially. Buying supermarket products with the ‘Red Tractor’ logo ensures that food and drink are produced in Britain. Buying local or direct from farm shops will help farmers.

During the pandemic, local businesses supplied customers with essential products and services that was unavailable in the supermarkets. However, many customers ultimately buy on price and could (unknowingly) turn to cheaper meat produced in other countries with less welfare and environmental standards to make savings on the household budget.

Longer-term ambitions of ‘levelling up’ the UK’s rural economy might also bridge urban-rural inequalities.

For farmers to economically prosper, they should operate in a conducive, not constraining, environment that allows for entrepreneurial activities to be explored. Skillsets can only take farmers so far - the wider rural economy should contain resources than enable entrepreneurial opportunities.

The kind of support outlined above will be helpful for farmers in responding to the on-going cost of living crisis, but could also help them prepare for the only thing that is certain in UK agriculture - future uncertainty.

Contact us

If you would like to get in touch regarding any of these blog entries, or are interested in contributing to the blog, please contact:

Email: research.lubs@leeds.ac.ukPhone: +44 (0)113 343 8754

Click here to view our privacy statement. You can repost this blog article, following the terms listed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the views of Leeds University Business School or the University of Leeds.