Implications of the latest Human Rights legislations relating to supply chains

- Centre for Operations and Supply Chain Research

It is estimated that over 40 million people are victims of modern slavery globally, with 16 million victims of forced labour in the private sector. Modern slavery, as described by previous Home Secretary, Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP, is “a brutal way of maximising profits, by producing goods and services at ever lower costs with scant regard for the terrible impact this has on individuals”.

To combat modern slavery, many new modern slavery and forced-labour transparency acts have been introduced around the world. There is now a new bill to amend the UK 2015 Modern Slavery Act. Other similar legislation on supply chain transparency and due diligence have been introduced in Germany, the United States, and the European Union, demanding more transparency and accountability.

However, many organisations are not ready to meet these more stringent and demanding regulations. It is hard for large enterprises to track forced labours in their supply chains, and even harder for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

To help organisations understand their liabilities and how to prepare, this blog discusses the implications of 19 acts introduced in Europe and North America between 2012 and 2023 (see Table 1). These acts are applicable to organisations of different sizes, scopes of the supply chain, the level of scrutiny and transparency required, and the different types of penalties. Our analysis shows that:

-

Most regulations are targeted at large multinationals

-

There are new regulations that cover SMEs and means to support them

-

New regulations cover both direct and indirect suppliers

-

There is an increased demand for a higher level of transparency

-

There is an increased emphasis on integrating supply chain due diligence policy

-

There are a variety of penalties for non-compliance.

Table 1. Supply chain transparency and human rights acts

NB. “Introduced” = the legislation is in its early stages ie a formal draft with further approvals still needed.

“Adopted” = a stage between introduced and enacted (made into law); the final approval may be required or may already be completed, but the legislation is not yet in place (ie it is yet to be enacted).

“Effective” = the legislation has been enacted; sanctions will be imposed if violations are made.

|

Year |

No |

Country/Region |

Legislation |

Status |

|

2023 |

19 |

European Union |

Adopted |

|

|

2023 |

18 |

Germany |

Effective |

|

|

2022 |

17 |

United States |

Introduced |

|

|

2022 |

16 |

State of California |

Effective |

|

|

2022 |

15 |

United States |

Fashioning Accountability and Building Real Institutional Change Act (FABRIC Act) |

Introduced |

|

2022 |

14 |

United States |

Effective |

|

|

2022 |

13 |

Norway |

Effective |

|

|

2022 |

12 |

Canada |

Introduced |

|

|

2022 |

11 |

European Union |

Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and Amending Directive |

Adopted |

|

2022 |

10 |

Switzerland |

Effective |

|

|

2021 |

9 |

UK |

Introduced |

|

|

2021 |

8 |

State of New York |

New York Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act |

Introduced |

|

2020 |

7 |

United States |

Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Act of 2020 |

Introduced |

|

2019 |

6 |

Australia |

Effective |

|

|

2019 |

5 |

The Netherlands |

Adopted |

|

|

2017 |

4 |

Italy |

Effective |

|

|

2017 |

3 |

France |

Effective |

|

|

2015 |

2 |

UK |

Effective |

|

|

2012 |

1 |

California |

Effective |

Most regulations are targeted at large multinationals

Figure 1 shows that most regulations apply to only large enterprises with a large global revenue and/or number of employees in the country. For example:

-

The Germany Due Diligence Act requires companies with more than 3,000 employees in Germany to submit due diligence reports in 2023; this number will be reduced to 1,000 in 2024.

-

The UK Modern Slavery Act involves corporations whose worldwide annual turnover exceeded £36M.

-

The Norway Transparency Act defines larger entities as those where "sales revenues achieved NOK 70M’ and/or ‘balance sheet total met NOK 35M’ and/or ‘more than 50 full-time employees."

-

The EU Due Diligence Directive considers EU companies with more than €150M worldwide turnover and more than 500 employees, as well as non-EU companies with €150M turnover generated in the EU. Two years later, the turnover thresholds will be reduced to €40M in high-impact sectors like textiles.

Figure 1. Which entity is liable and what supply chain scope?

The EU Due Diligence Directive is restricted to only large enterprises because they are more exposed to higher adverse impacts than SMEs, but as large buyers they are expected to pass on the regulatory burdens to their small suppliers. Some acts eg the US Slave-free Act and US Transparency Act, require large enterprises to ensure the audits of their suppliers. It is hard to delegate audit responsibilities to low-tier suppliers, some of which are SMEs.

Four new regulations cover SMEs

Figure 1 shows four new regulations that require both large enterprises and SMEs to comply; The EU Product Ban, US UFLPA, Canada C-262 and Netherlands Child Labour Act are applicable to an entity of any scale. There is guidance for SMEs regarding these regulations:

-

The US UFLPA Entity List was published to guide importers to identify risks.

-

The US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) generated "operational guidance for importers" to help companies, especially SMEs, respond to the CBP’s request.

-

EU Product Ban planned to support SMEs by issuing a registry of penalized and banned entities and products. There will be specific "design of the measure" for SMEs eg risk-based enforcement and support tools.

-

The Netherlands Child Labour Act contains a provision that certain categories of companies from low-risk sectors or small companies can be exempted.

-

Canada C-262, introduced in 2022, is still at an early stage as a private member’s bill and has no further explanation related to SMEs. So, a specific public list of high-risk entities, risk-based enforcement, and support tools shall be used to help SMEs.

From vague “supply chains” to direct and indirect suppliers

Some earlier regulations use the term “supply chains” without clarifying its scope. The UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 defines its scope as "any part of the supply chain". This isn’t clear how far upstream (the process of getting materials to the manufacturer) the supply chain is, but the amendment bill in 2021 clarifies suppliers or sub-suppliers should be involved.

For most new regulations, large enterprises are expected to cover both direct and indirect suppliers. ‘Indirect suppliers’ or ‘subcontractors’ are mentioned in several regulations (eg US Transparency Act, Germany Due Diligence Act, EU Due Diligence Directive, Norway Transparency Act), yet few clarify how many tiers of suppliers are involved.

The New York Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act uses the terms "tier-n suppliers" while the US Slave-free Act refers to "secondary suppliers", which, whilst still being vague, are an improvement on the term “supply chains”.

Figure 2. Level of scrutiny and transparency

Reporting on websites or official portals

Figure 2 shows that some regulations simply require enterprises to produce a statement or annual statement on their websites, with a few exceptions:

-

The Italy No. 254 Act requires parent companies to publish a nonfinancial statement, including subsidiaries information, as part of the directors’ report, part of the annual report, or a separate report, rather than supply chain information.

-

California’s Garment Worker Protection Act and the US FABRIC Act requires every entity engaged in garment manufacturing to register on an official website.

Report upon request or assessed when suspicious

In some cases, entities do not need to publish public information or statements. However:

-

US UFLPA 2022 requires importers of any size to respond to Customs and Border Protection requests demonstrating that the goods are not produced wholly or in part by forced labour in Xinjiang, China.

-

For the EU Product Ban 2023, in principle, the "competent authority" can investigate any entity anytime based on their own assessment using validated information from other parties, including any natural or legal persons, other relevant authorities, the verified external database, etc. Such entities are expected to cooperate and provide information to the investigation.

Due diligence (DD) reports have become common

DD reports increase the level of transparency and monitoring of the effectiveness of actions and tracking of their implementation. From 2021, many new regulations require entities to demonstrate that they have and follow a DD policy and procedure on their websites.

DD obligation applies to almost all the 16 Acts in Figure 2, except the EU Product Ban (2023), which relies on public governance and official competent authorities to assess.

Most such self-regulation reports are expected to disclose efforts taken to evaluate and assess risks.

-

The US Slave-free Act only requires policies information used to evaluate and address risks.

-

US UFLPA requires information assessing and preventing forced labour risks related to Uyghur.

Some regulations require information about mitigation and prevention actions, eg UK Modern Slavery and Amendment, US Supply Chain Transparency Act, Australia Modern Slavery Act, etc.

Increasing levels of transparency and scrutiny

The level of detail about DD progress or procedures varies. Some regulations eg US Supply Chain Transparency, require entities to ensure audits of suppliers and specify whether the audits are carried out by third parties, but there is no need to publish audit results. It becomes more transparent when the findings of audits are made public.

The US Slave-free Act requires entities to document findings from each audit to the supervisory body and at their websites. The UK Amendment Bill mentions the use of credible external auditors.

Integrating DD and supply chain responsibilities

Entities cannot treat DD reports on websites as lip service. There are new regulations that require companies to handle DDs in different ways, such as:

-

Integrating DD into their policies and management systems (Norway, EU DD, New York)

-

Mapping their supply chain (New York, France)

-

Assigning DD responsibility to directors (EU DD & Switzerland)

-

Requiring chief executive officers to sign certifications to confirm compliance to the act and exercise of DD policies and procedures in order to eradicate forced labour in their supply chain (US Slave-free Act)

-

Requiring suppliers to provide certifications (also the US Slave-free Act).

There is a trend to increase responsibilities from disclosing policies and actions to evaluate and address risks, to disclosing monitoring of the effectiveness of measures taken, to embedding responsible business conducts into the entities’ culture and the supply chains.

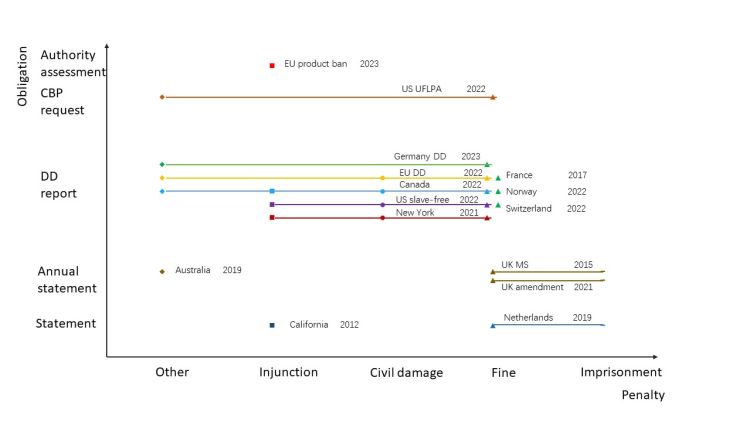

Figure 3. Penalty

Imprisonment for statements

Some of the early regulations use imprisonment to penalise offenders:

-

The Netherlands Child Labour Due Diligence Act clarifies that two violations within five years would lead to the imprisonment of the responsible director for up to two years.

-

The UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 states that "on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for life" or "on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months" for offence of forced labour. Its amendment bill changes the clause to "on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years".

What if organisations failed to comply with the regulations? Those more serious penalties are often applicable to large enterprises who failed to publish statements on their website rather than the poor quality of statements. When the levels of scrutiny and transparency increase, punishments such as fines, civil damages, and injunctions become more common.

Fines are the most common punishment

Some acts involve hefty fines. For example:

-

The Germany Due Diligence Act and New York Fashion Sustainability Act fine up to 2% of a company’s annual revenue

-

The UK Amendment Bill fines up to 4% of global turnover (to a maximum of £20 million).

In some cases, no amount of fine is declared eg the France Vigilance, Norway Transparency Act. The EU Due Diligence Directive adopts "pecuniary sanction based on the company’s turnover".

Civil damages and injunctions eg product bans

Civil damages are adopted by some latest acts which require DD reporting, including: EU Due Diligence Directive, New York Fashion Sustainability Act, Canada C-262 and US Slave-free Act. New York Fashion Sustainability Act, Canada C-262 and US Slave-free Act use general injunctions as well. Some specific injunctions are clarified, for example, products made by forced labour would be prohibited or withdrawn or disposed of by the EU Product Ban. The California Transparency Act would order a company to add or change transparency information on its website.

Other penalties

There are several other forms of penalties for companies that do not comply with the acts. For example:

-

The Germany Due Diligence Act excludes offenders from public procurement.

-

The Canada C-262 withdraws any government support or funding until the entity complies with the act. Such sanctions can be made public.

-

The EU Due Diligence Directive requires authorities to publish their decision of sanction, “naming and shaming”.

-

In the Australia Modern Slavery Act, failure to provide information, including the identity of the entity, would be published on the official register or elsewhere.

-

The US UFLPA aims to prevent the importation of forced labour goods, so goods detention or seizure are applied. The US Slave-free Act, however, has no description about enforcement in the bill.

Concluding remark and future research

Human rights transparency and supply chain due diligence regulations will only get more stringent. We will continue our research with a focus on understanding how large and small enterprises prepare for such regulations, and how they work with upstream suppliers to jointly eradicate forced and child labour.

If you are interested in this research, either to collaborate or to provide expert opinions, please contact Professor Chee Yew Wong (research.lubs@leeds.ac.uk).

Contact us

If you would like to get in touch regarding any of these blog entries, or are interested in contributing to the blog, please contact:

Email: research.lubs@leeds.ac.ukPhone: +44 (0)113 343 8754

Click here to view our privacy statement. You can repost this blog article, following the terms listed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the views of Leeds University Business School or the University of Leeds.