International Women’s Day 2019 – a spotlight on our research

- Centre for Employment Relations, Innovation and Change

International Women's Day (IWD) celebrates the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women around the world. While highlighting the many achievements made, it also acts as a call for acceleration of progress towards gender equality in all aspects of public and private life. This year’s theme is better balance, highlighting the many ways in which greater gender balance can benefit individuals, communities, societies and economies around the world.

In the UK, 2018 was a significant year with gender equality dominating the media. The introduction of the requirement for companies in the UK with over 250 employees to publish their gender pay gap (GPG) attracted huge media attention and in doing so sparked extensive debate about the many causes of the GPG, and the extent to which inequalities between women and men exist in organisational settings. While the introduction of the new regulation is encouraging, how organisations take action to tackle their GPG, remains to be seen. Lack of gender balance in the types of jobs women and men undertake within the same organisation, differences in pay rates for women’s and men’s jobs, as well as a lack of gender balanced leadership are challenges many companies continue to face.

Beyond the organisational level of analysis there are deeper concerns about the pace of change towards gender equality. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report compiles data on key thematic areas of economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment. Each year the Report finds that no country has achieved full equality between women and men, and in 2018 the report only finds ‘marginal improvement’, with a gender parity gap of 32%.

The size of gaps do of course vary significantly across countries. Many European countries have the smallest gender gaps. For many academics concerned with gender equality, there is much we could learn from our European neighbours. Furthermore, many academics focused on gender equality share the view that the EU has been a powerful and progressive force for change. In the face of Brexit, there are very real and pressing concerns about gender equality policy, and in particular the disproportional effect women may experience as workers, users of public services and as primary caregivers. The Women's Budget Group claim that women who are most disadvantaged and vulnerable may experience the greatest hardship through cuts to jobs, services and reduced legal protections.

The Centre for Employment Relations Innovation and Change has a critical mass of researchers who are committed to researching gender alongside wider social, political and economic inequalities. Jo Burgess, Jack Daly and Cheryl Hurst engage with the theme gender balance (or absence thereof) in educational opportunities, pay and leadership. As the World Economic Forum report highlights, together these are critical indicators central to the advancement of gender equality across the world. Here they speak about the motivations for their doctoral research and their ongoing work in this area.

Occupational gender segregation in vocational education and training - Joanne Burgess

The improved educational attainment of women, achieved over consecutive decades, has yet to be fully realised in employment opportunities and outcomes. Despite women’s significant educational achievements, pay parity has yet to be realised. The Commission for Employment and Skills identifies that gender is still a key determinant of both occupational choice and the value ascribed to occupations.

Career choices which perpetuate occupational gender segregation (a major cause of the gender pay gap) have their origins in childhood socialisation and education. Research for Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission finds that non-graduate women experience a severe impact on pay as a result of having children. This is particularly problematic for those who have undertaken vocational education and training routes, as women are concentrated in sectors with lower pay and a scarcity of ongoing training and development opportunities.

Policies such as National Living Wage and Universal Credit may have negative impacts on women’s participation in the labour market because they may stifle pay progression by flattening hierarchies in some non-graduate roles, and in the case of Universal Credit, penalise second earners. Additionally, there is a dearth of policy initiatives that support the entry of women into occupational areas that have traditionally been male dominated. The continued occupational gender segregation in vocational education and training maintains and perpetuates disadvantages which shape women’s lives.

The impact of educational choices defines opportunity and life chances so the role of the state in advancing equality for women in education and employment needs to begin with governmental commitment and policy to address how education is structured and delivered. Target setting is commonplace in education for the management of outcomes, finances and quality but has not been utilised in determining labour market outcomes through remedial use in formative settings. In order to address the woeful lack of progress in reducing occupational gender segregation the use of targets for educational providers and employers, albeit a blunt instrument, could accelerate change.

Equally, it is accepted wisdom that role models can make significant impact in forming and changing young peoples’ perception of their career options and occupational choices, but the problem remains that widespread engagement with this strategy is hindered by the lack of people within the labour market who have made atypical career choices.

Action to address labour market imbalance needs to begin with an acknowledgement that career options are frequently defined by gender, ethnicity and social class, and as such the route to greater equality is through policy strategies which directly seek to dismantle the social, economic and cultural bases of inequality. The potential for change must start with our education system.

My PhD research explores the persistence of occupational gender segregation in vocational education and training with a focus on the intersection between gender and social class in defining the career choices of young people. It is motivated by the challenges and barriers to social and educational change I saw in my work in the further education sector but also by frustration that the equalitarian future I imagined as a teenager has not been realised, and a strong desire to ensure that my child determines her future without limitations.

Gender neutrality in education requires a rethinking of curriculum in all phases to tackle the cycle of occupational segregation. A central aim of education should be to embolden children to see themselves as beyond the constraints of gender and social class. This requires policy for education that focuses on developing the innate skills, qualities and competences of a child for life. Education should be at the vanguard of social change, challenging the normative values and assumption, empowering young people to make career decisions free from convention.

Understanding the Gender Pay Gap through Hegemonic Masculinity – Jack Daly

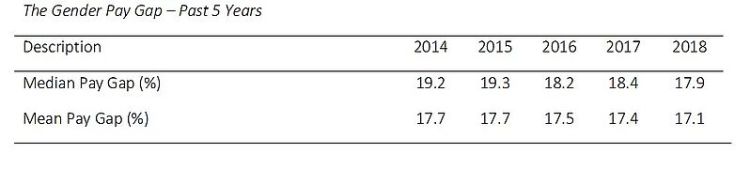

Equal pay for men and women is a major issue for organisations and wider society. Historical and current pay inequalities maintain male superiority within work, limiting female career opportunities, economic agency and independence. Gender pay gaps are persistent and despite recent government policy and media attention, only marginal improvements have been observed.

Coinciding with mandatory reporting of pay gap information for organisations with greater than 250 members of staff and in line with the Equality Act 2010, the UK Government has outlined 16 actions points to address the gender pay gap. Measures such as skill-based assessments, pay and promotion transparency and the appointment of diversity managers highlight positive actions organisations can take. However, significant drivers of the gender pay gap, such as occupations segregation, are not addressed despite evidence of pay inequalities across male and female jobs and occupations, and in particular the undervaluation of women’s work.

Take Tesco for example, who have recently faced a £4bn equal pay bill. Predominantly female shop floor workers conducted roles which required equivalent skills, demands and job characteristics as predominantly male warehouse workers who were paid approximately £5,000 more per year. These instances of historical pay differentials are often difficult to remedy within existing policy frameworks and where male and female staff are paid differently for work of equal value, it has often fallen to individuals and unions to challenge this. Furthermore, a lack of enforced penalties for incorrectly reported pay gap information may reduce how effective legislation is, but also the motivation for organisations to report accurately gender pay gaps. To more effectively address gender pay gaps, organisations must be open to reviewing, understanding and auditing pay.

Deconstructing gender within organisations may assist in understanding the true drivers of the gender pay gap. Hegemonic masculinity positions male behaviours as the dominant and legitimate way of working within organisations. Behaviours such as assertion, autonomy and competition are desired within organisations whilst being stereotyped as naturally male. Where informal social networks communicate these values between individuals within organisations, men may receive better access to resources and opportunities. Furthermore, where stereotypes of gender roles are reinforced within organisations, women may find themselves disadvantaged within their careers. For example, if women are perceived as being unable to dedicate similar hours and commitment as men they may experience what is commonly referred to as the ‘glass ceiling’.

My research investigates how hegemonic masculinity can further our understanding of the causes of the gender pay gap. Masculine behaviours have historically been attributed with organisational success, and the extent to which this remains the case and is rewarded through organisational pay will be explored. Governmental regulation provides a positive step to address the gender pay gap. However, the historically based social structures that advantage males must be exposed to understand the drivers of the gender pay gap. The legitimacy of masculine workplace practices needs to be problematised and transformed to create more human-centric behaviours that recognise the value of both male and female skills and talents.

Women in leadership: progress and future steps – Cheryl Hurst

Achieving gender balance in leadership positions is a work in progress. It requires continuous effort to ensure equal rights and opportunities are afforded to both women and men within the labour market.

While there’s been rightful celebration of successes thus far, there are still improvements to be made and milestones to hit. When looking specifically at leadership, we’ve seen progress in the drive to improve representation in the UK’s largest companies. There are fewer all male boards than ever before, with a ‘naming-and-shaming’ move by investors against boards of the FTSE 350 without at least a 25% female board. These changes stem from the continuous effort from companies in the FTSE 350 to hit the latest government-backed target of 33% of board positions being occupied by women by 2020. Although research indicates we may fall short of this target, there are still positives to be taken from the successes so far, particularly in that there is an increased acceptance that improved gender equality in decision making positions makes good business sense. The focus for research, therefore, can continue the shift from justifying why greater gender balance is necessary, towards how we quicken the pace in getting there.

The Quota Question

Following the 2015 success of achieving the 25% target set by Lord Davies, the 2016 female FTSE board report celebrated the UK as a role model for achieving greater gender balance on corporate boards. A key tenet of the report was the different approaches of targets and quotas, highlighting the benefits of targets for cultural, long-lasting, change. Quotas were deemed as “incongruent with the UK’s approach and business culture”. More recently, the 2018 board report articulated a shift in view on the implementation of quotas in UK corporations. Referred to as a change from opposition to proposition, some of the participants interviewed were now more open minded to the idea. While the UK remains quota-free for its gender equality goals, changing views on quotas allow space to reinterpret what it means to be meritocratic and fair, as well as an evolving view of whose responsibility it is to ‘solve’ inequality.

Oppositions to quotas cite issues related to meritocracy and fairness; where positions should go to those most deserving, and not to those who are members of particular underrepresented groups. While these concerns are valid, there’s an increasing recognition that current positions are not necessarily made based on merit or fairness, but are representative of deep-rooted historical bias. We also cannot hope to see gender balance in leadership positions or in the executive pipeline any time soon if we continue at the current pace of change, especially since this has slowed in terms of female appointments to FTSE250 boards.

Quota Research Trajectory

My own PhD research on changing views towards quotas in leadership positions finds that leaders are not as deeply opposed to quotas as previously thought. Through interviews with senior leaders in public institutions, the ‘for or against’ quota argument is not so clear cut. When asked about their views on quotas, many of the participants interviewed were hesitant, but acknowledged that there is a place for government legislation should the progress not improve in the very near future; provided quotas are redesigned to make them work better as shown by Apolitical. Some participants, however, were clear in their support of a shift towards a quota system. In the words of one female senior leader:

I'm a big fan of quotas. I'd like quotas but that's an unpopular admittance. I talk to senior women who are now older than me and they've been waiting a long time and a lot of them will say to me you know when I was young I was just like ‘No I don't want tokenism, I want to be there on my merits, I don't want quotas... but now I'm sick of waiting, I want quotas. Speed it along.

Contact us

If you would like to get in touch regarding any of these blog entries, or are interested in contributing to the blog, please contact:

Email: research.lubs@leeds.ac.ukPhone: +44 (0)113 343 8754

Click here to view our privacy statement. You can repost this blog article, following the terms listed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the views of Leeds University Business School or the University of Leeds.