Young Germans are tuning out of politics

- Centre for Employment Relations, Innovation and Change

Every third German between 18 and 30 years old considers themselves to be in a “precarious” position, engaged in temporary, unstable or non-standard employment. This is happening against the backdrop of the glorious reputation of the German training and education system, low unemployment rate and comparatively generous welfare state.

And with an election just days away, question marks remain over this group. Will they radicalise, and support populist parties? Will they stay away from the polls altogether?

Economic uncertainty has disproportionately affected young workers, who are far more likely to find themselves in unstable employment than their older counterparts. Overall, 54% of employees between 15 and 24 work in atypical employment – 53% are on temporary contracts while a further 4% are self-employed.

We surveyed 1,000 Germans between the ages of 18 and 30, and found that economically insecure young people are more at risk of feeling estranged from politics. People in insecure employment are significantly more likely to be an undecided voter or to not vote at all.

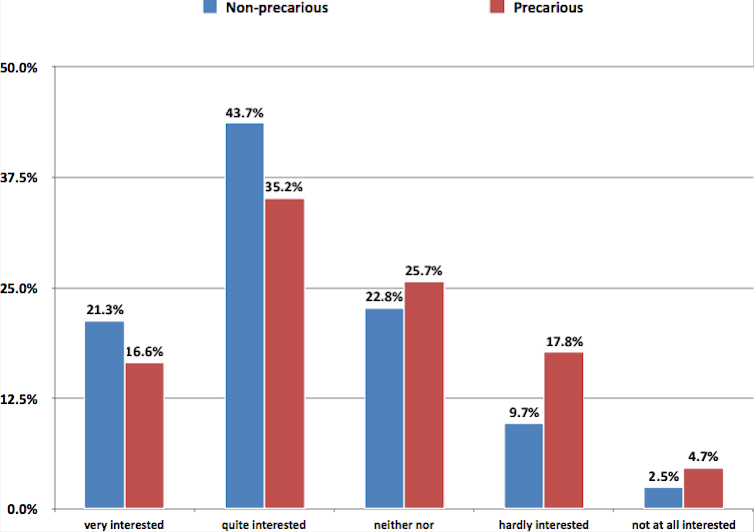

They are almost twice as likely to be uninterested in politics as young people in secure employment. And they are more frustrated: up to 40% of them say they can’t change anything with their vote – compared to only 16% of young people in secure work.

Support for Angela Merkel’s CDU is lower among young people in insecure work than among the general German population. However, 26.8% said they still intended to vote for her. That compares to the national estimate of 37%.

The social-democratic SPD is still the second strongest party. Yet its support is on the wane thanks to its “Agenda 2010” – a policy introduced when it was in government that launched labour market reforms enabling precarious forms of work in Germany. Only 14% of our group of young insecure workers would vote for SPD compared with the 20% projected share among the general population.

Not into smaller parties

The German election system is representative. Parties with more than 5% of the vote get seats in the lower house of parliament. This year, four additional parties are likely to make it into parliament.

Alternative for Germany (AfD), a right-wing nationalist party is expected to secure 12% of the vote. Our survey shows AfD enjoys only a modest 4.3% support among young Germans, a share that does not increase among those out of stable work. The Liberals (FDP), who were absent from the lower house during the last legislative period, may get 9% of the youth vote, matching the predictions of the general vote – though we see much less support among young people in precarious work.

Left parties like the DieLinke or Greens get slightly higher shares of votes among young people in precarious work compared to people in stable work. Together, the smaller parties do get 5% of votes among young people but none attracts enough support to make it into parliament alone.

Reluctantly backing the status quo

Young Germans in precarious positions can’t seem to find a political party that represents their interests so they are likely to stay away from politics and elections. Surprisingly, if they do vote, they do as a majority support centre-right parties.

Politically, Angela Merkel has attracted a lot of support and respect for her open borders policy towards refugees. She is also credited with modernising the CDU, enabling the right to same sex marriage and making it legal for same-sex couples to adopt. Merkel’s CDU is a less conservative party than that of Helmut Kohl, which may be why it appeals to our group when they do vote.

At the same time, the Social Democrats have moved towards the middle and lost their distinct profile as a workers’ party committed to social justice.

A sociological explanation for this situation would be that precarity has already become part of an accepted new normality that the young generation does not rebel against. Rather than trying to change their lot with their vote, they turn their back on politics. They may come to change their minds on this point, but it doesn’t seem likely for this election.![]()

Vera Trappmann, Associate Professor in Work and Employment Relations, University of Leeds and Danat Valizade, Lecturer in Quantitative Methods, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Contact us

If you would like to get in touch regarding any of these blog entries, or are interested in contributing to the blog, please contact:

Email: research.lubs@leeds.ac.ukPhone: +44 (0)113 343 8754

Click here to view our privacy statement. You can repost this blog article, following the terms listed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the views of Leeds University Business School or the University of Leeds.