What role can local government play in the future of warehousing work?

- Centre for Employment Relations, Innovation and Change

This article originally featured on the Digital Futures at Work Research Centre website and has been reposted here with permission.

The digital transformation of work involves technological changes that affect everyday jobs and every local community. While the risks and opportunities of AI are the focus of intense national policy debates, our research suggests that the impact of new technologies on jobs should be higher on the agenda for local government.

This is because local government actors can play a significant role in mitigating negative impacts of technological change on workers. They can work with businesses, including through leveraging significant amounts of grant funding, to encourage more positive outcomes that help to secure good jobs and identify future skills needs.

These issues are particularly important in warehousing and logistics work. In our region, Yorkshire and the Humber, warehousing has become an increasingly significant source of employment, but the issue of technological change poses some dilemmas that have been relatively overlooked by policy makers, stakeholders and the media.

Time spent reading warehousing industry trade and consultancy literature, attending industry events, or perusing the marketing materials of technological providers quickly reveals a range of technological solutions claiming to automate almost all aspects of warehousing work. These ‘solutions’ offer increasingly sophisticated ways of re-engineering warehousing workplaces in pursuit of faster fulfilment times and fewer errors. Examples include automated guided forklifts and other types of robots facilitating goods-to-person picking, automated retrieval systems for items stores in dense grid systems, and AI-enabled warehouse management systems.

However, claims of technological sophistication in warehousing, much like in other sectors, can at times be overstated. Technologies that have been around for a number of decades – for example, handheld scanning devices, manned forklifts and reach trucks, and vast networks of conveyor systems – are still widely used and considered to still be fit for purpose.

How much do local governments know about warehousing work?

In localities that rely on warehousing jobs, our research asks how technological transformations are changing the nature of warehousing work, in terms of the skills required, the people employed, and the physical and mental demands placed on workers. As part of our current research, we set out to engage with a range of stakeholders, including local government, to get a sense of how they perceive the sector and where it fits with future plans for economic development across the region.

Questions about the digital transformations of working life are a major priority for local government, and these are especially complex in warehousing. Often, warehousing firms are enigmatic when viewed from local councils’ perspectives, with many council officers feeling they have little concrete information about ‘what goes on within the big grey boxes’. The likely implications of automation and digital technologies in warehousing workplaces therefore remain opaque.

What future for warehousing work in Yorkshire?

As we developed a growing understanding of the stakes of these discussions in Yorkshire, especially given that warehousing is often concentrated in regions suffering the effects of deindustrialisation, we quickly became sensitised to the role of local government in shaping the future of work in the sector. One of our key research objectives is to explore how local government can intervene to influence work-related outcomes in a sector where technological change is constantly evolving but is also uneven and unpredictable.

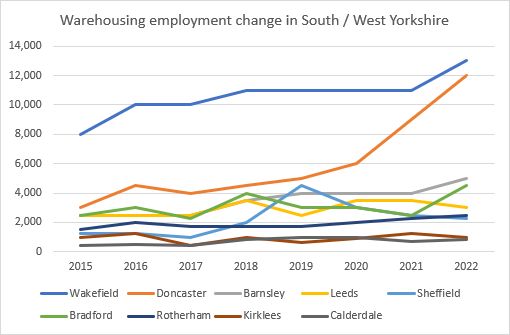

Yorkshire and the Humber is comprised of four sub-regions, yet warehousing and logistics work remains concentrated along major transport veins in the West and South (notably Wakefield, on the junction between the M1 and M62). Employment in the sector has increased significantly in recent years, attracting attention from local policy makers. In certain localities, such as Doncaster situated on the A1(M), the number of jobs in warehousing grew by 300% between 2015 and 2022 (see Figure 1).

Local government actors often feel conflicted about the rise in warehousing in the region. Some suggest that the sector provides necessary entry-level jobs to those in the population whose highest qualification is NVQ1 or have no formal qualifications. This is currently 17.9% of people aged 16-64 in Yorkshire and the Humber (only slightly above the national average of 16.6%). However, in Wakefield and Doncaster, where warehousing is most densely concentrated, qualification levels are within the lowest 20% nationally.

Simultaneously, however, many officials express concerns about what the future holds within the sector; especially in terms of technological change and what impact this could have on the availability and nature of the work that might remain. For example, if new sites open that require fewer workers because of the use of automating technologies or existing roles are replaced then this might cause issues within localities which rely heavily on this type of work.

Warehousing work tends to feature comparatively high rates of turnover. Is there a danger that, even where job numbers remain robust, the sector offers work with comparatively few opportunities for upskilling and career progression, conditions which can lead to high rates of employment ‘churn’?

Figure 1 Authors’ analysis: Business Register and Employment Survey (2022)

How can local government shape the future of warehousing work?

Our initial findings indicate that there is a clear desire among local government actors to play a more proactive role in the future of warehousing work in Yorkshire.

As the HuLog project evolves, we will provide evidenced recommendations for local government to help inform their approach to the sector. Clearly, local government’s capacity is limited because of years of budget constraints. More resources are needed if local government is to play a bigger in the future of the sector.

However, there are several areas where local government actors may still be able to exercise significant influence to mitigate the potential negative impacts of technological change on workers (such as job replacement, work intensification, deskilling, etc.) and amplify the potential positive ones (such as opportunities for upskilling and easing the physical demands of the work).

Here are two examples of a wider set that we hope to disseminate over the course of the project:

1. Business support resourcing

Councils and combined authorities spend substantial resources on supporting local businesses on employment-related issues, including through grant funding. However, this kind of support is rarely used to lever better work-related outcomes. Indeed, across the region, there is not a widely-used definition of ‘good quality work’ that could be referenced in these decisions. Nevertheless, the Fair Work Charter currently being rolled out within West Yorkshire could go some way in addressing this. Could local authority support be more targeted to generate better work-related outcomes, such as commitments to provide stronger training and career pathways, or norms around flexible working? A first step here would be a clearer, measurable, and shared definition of good quality work that can be used in benchmarking employment outcomes across the region and beyond.

2. Skill strategies

Local authorities need better tools for encouraging local businesses to engage in discussion of skills provision and, critically, forecasting future skills needs. Other stakeholders such as trade unions and employment support agencies should also be embedded in these discussions, enhancing social dialogue between groups interested in shaping a more sustainable future for the sector. This would enable local government to plan its skills initiatives more effectively, especially around digital skills that are a particular priority in regions like West Yorkshire. We will also consider whether national government could place new requirements on businesses to engage with local authorities on questions such as long-term skills planning.

Supporting local government actors to be more proactive in these areas could help redistribute some of the power needed to shape the future of warehousing work and ensure that digital technological transformations work to the benefit of local populations.

Contact us

If you would like to get in touch regarding any of these blog entries, or are interested in contributing to the blog, please contact:

Email: research.lubs@leeds.ac.ukPhone: +44 (0)113 343 8754

Click here to view our privacy statement

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the views of Leeds University Business School or the University of Leeds.